Last Monday I posted a short adaptation of an extract of Portrait of the Artist and promised an essay to accompany. Now, the thrilling conclusion. This will cover the cinematic aspects of his aesthetic and comparison to aspects of my adaptation, as well as looking at a number of multi-layered image films.

————————

James Joyce has been described as the “most cinematic” of the modernist writers. As one of the “foremost representatives” of the movement, it seems fitting his work parallels film, the most “modern” medium of his time, both defying traditional forms of representation. As well as their mutual focus on visual experimentation, much of Joyce’s  style is directly comparable to cinematic technique. His imagery often draws on the relationship of light and shadow, even from his earliest childhood works. While his luminous imagery may have begun in the era of the zoetrope and magic lantern, the more complex optical descriptions in Joyce’s later work contain direct parallels with cinema itself. Specifically, this essay will examine 1914’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Here, such cinematic imagery is mixed with another filmic technique: the flexibility of time. Portrait’s temporal continuity is fluid, as the novel smoothly transitions between periods of its protagonist’s life, allowing the reader to “literally wander about in time, as if it were part of a solid and seemingly permanent landscape.” This temporal fluidity is a central tenet of the cinema. Within the plot of a typical film there are often flashbacks and flash-forwards, but even the most basic film editing requires the combination of scenes and shots filmed at different times. This renders any film into a collection of different moments, similar to Stephen Dedalus’ fragmented history in Portrait. The novel’s temporal jumps, as well as its particularly cinematic imagery, are most notable when the narrative becomes a subjective memory of earlier events. This essay will therefore examine these extracts in order to explore the novel’s relationship with the cinema, and will attempt to bridge the gap between existing critical theory on both Joyce and film through their mutual association with the faculty of memory.

style is directly comparable to cinematic technique. His imagery often draws on the relationship of light and shadow, even from his earliest childhood works. While his luminous imagery may have begun in the era of the zoetrope and magic lantern, the more complex optical descriptions in Joyce’s later work contain direct parallels with cinema itself. Specifically, this essay will examine 1914’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Here, such cinematic imagery is mixed with another filmic technique: the flexibility of time. Portrait’s temporal continuity is fluid, as the novel smoothly transitions between periods of its protagonist’s life, allowing the reader to “literally wander about in time, as if it were part of a solid and seemingly permanent landscape.” This temporal fluidity is a central tenet of the cinema. Within the plot of a typical film there are often flashbacks and flash-forwards, but even the most basic film editing requires the combination of scenes and shots filmed at different times. This renders any film into a collection of different moments, similar to Stephen Dedalus’ fragmented history in Portrait. The novel’s temporal jumps, as well as its particularly cinematic imagery, are most notable when the narrative becomes a subjective memory of earlier events. This essay will therefore examine these extracts in order to explore the novel’s relationship with the cinema, and will attempt to bridge the gap between existing critical theory on both Joyce and film through their mutual association with the faculty of memory.

While written in third person, Portrait is a strong example of “sustained intra-diegetic focalization”, as all of its events are mediated through the consciousness and “mobilized virtual gaze” of Stephen. Its imagery therefore exists on different layers of interiority, with memory constituting one of the deepest. Cinematic visuals permeate all of these levels, starting with the most superficial: Stephen’s immediate perception of the external  world. The experience of watching other boys playing football is described: “Then Jack Lawton’s yellow boots dodged out the ball and all the other boots and legs ran after.” The legs and boots appear independently to the boys they belong to. This example of synecdoche also parallels the cinematic close-up. Often parts of the body will be shown alone, as the action cuts between them , fragmenting the body in a similar way to Joyce’s language.

world. The experience of watching other boys playing football is described: “Then Jack Lawton’s yellow boots dodged out the ball and all the other boots and legs ran after.” The legs and boots appear independently to the boys they belong to. This example of synecdoche also parallels the cinematic close-up. Often parts of the body will be shown alone, as the action cuts between them , fragmenting the body in a similar way to Joyce’s language.

Stephen’s perceptions again parallel film when his glasses are broken and “the fellows seemed to him smaller and farther away and the goalposts so thin and far and the soft  grey sky so high up.” Keith Williams compares this distorted image to a similar scene in F.W. Murnau’s 1924 film The Last Laugh, in which a janitor’s vision is similarly obscured due to poor eye-sight, with his struggle to read forcing a letter’s contents to appear as individual words. These are objective “facts” of Stephen’s world, however; the next layer of his interiority comes from his interpretation of such experiences. When performing a play:

grey sky so high up.” Keith Williams compares this distorted image to a similar scene in F.W. Murnau’s 1924 film The Last Laugh, in which a janitor’s vision is similarly obscured due to poor eye-sight, with his struggle to read forcing a letter’s contents to appear as individual words. These are objective “facts” of Stephen’s world, however; the next layer of his interiority comes from his interpretation of such experiences. When performing a play:

“He found himself on the stage amid the garish gas and the dim scenery,

acting before the innumerable faces of the void. […] When the curtain fell

on the last scene he head the void filled with applause and, through a rift in

side scene, saw the simple body before which he had acted magically

deformed, the void of faces breaking at all points and falling asunder into

busy groups.”

The break-up of this “void of faces” has been compared to a cubist painting, such as Picasso’s Girl with a Mandolin as both feature an amorphous whole comprised of discrete shattered elements. The cinema again seems to have the most relevance, however, as Joyce’s imagery implies a process rather than an instant. Instead of a painting, this seems more comparable to the surreal multi-frame images of Alberto Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures (1924), for instance a crowd of eyes all constantly moving and watching, and a photograph of a group being torn apart.

These examples only show Stephen’s mediation of the external world in the present moment. Joyce’s techniques in Portrait stretch beyond that, for example into dream  sequences, the most notable being when Stephen is taunted by Satyrs, similar to many early trick films of demonic transformation. Due to these dreams being wholly fictional constructions, the representation of memory is rendered unique due to its transformation of the real. Joyce’s manipulation of memories takes events which have occurred and defamiliarises them, turning simple human moments into visually dynamic experiences. Such memories “pass sharply and swiftly before [Stephen’s] mind”, almost becoming his reality as he retreats within them to the point that he must be re-awoken by a violent external influence. When remembering his arrival to Clongowes, Stephen is unaware of a loud football match around him, only brought back to the present by being “caught in the whirl of a scrimmage”. This implies that the memories overlay on top of Stephen’s current experiences, obscuring his view.

sequences, the most notable being when Stephen is taunted by Satyrs, similar to many early trick films of demonic transformation. Due to these dreams being wholly fictional constructions, the representation of memory is rendered unique due to its transformation of the real. Joyce’s manipulation of memories takes events which have occurred and defamiliarises them, turning simple human moments into visually dynamic experiences. Such memories “pass sharply and swiftly before [Stephen’s] mind”, almost becoming his reality as he retreats within them to the point that he must be re-awoken by a violent external influence. When remembering his arrival to Clongowes, Stephen is unaware of a loud football match around him, only brought back to the present by being “caught in the whirl of a scrimmage”. This implies that the memories overlay on top of Stephen’s current experiences, obscuring his view.

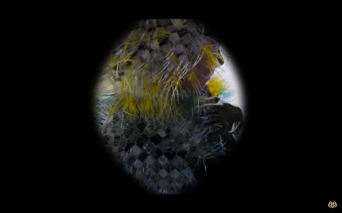

The most explicit example of this occurs during his friend Davin’s story of a flirtatious young woman. After Davin concludes, Stephen’s impressions of this woman are replayed upon the faces of those he passes: “The last words of Davin’s story sang forth in his memory and the figure of the woman in the story stood forth reflected in other figures of the peasant women whom he had seen standing in the doorways”. Upon being approached by a flower girl, Stephen perceives: “her young blue eyes seemed to him at the instant images of guilelessness, and he halted till the image had vanished and he saw only her ragged dress and damp coarse hair and hoydenish face.” This layering of the two girls’  faces creates a multi-layered image, one covering the other. In silent cinema, this effect was comparatively common, for example allowing the camera to tower over cities in Man with a Movie Camera (1929). A more technological connection can be extracted from Alan Speigel’s claim of Ulysses’s ‘Circe’ episode, that Joyce “projects the unconscious life of his protagonists outward, and all memory and desire seem to shift and glide before the eye of the reader in a dramatic and fully externalized form.” The connection of thoughts and “projection” can also be seen during the memory sequences of Portrait. Remembering often occurs in conjunction with the imagery of light sources, such as when Stephen thinks back to “the firelight on the wall of the infirmary where he lay sick”. The light helps to ‘cast’ the memory back into Stephen’s consciousness, as a cinema projector similarly reclaims the past by reproducing its image. Another example can be seen when Stephen remembers his childhood appearance: “It was strange to see his small body appear again for a moment: a little body in a grey belted suit.” This idea of Stephen seeing himself as a distanced external image adheres strongly to an aesthetic of projection. Finally, specific memories are also framed like cinematic shots. When thinking of his friend Cranly, Stephen can “never raise his mind the entire image of his body, but only the image of the head and face.” As with the legs and feet being cut off during the football match, this disconnected head is reminiscent of the camera frame cutting off parts of the body. These are only a small number of examples, but Joyce’s imagery of memory throughout the novel appears consistently comparable with equivalent cinematic techniques.

faces creates a multi-layered image, one covering the other. In silent cinema, this effect was comparatively common, for example allowing the camera to tower over cities in Man with a Movie Camera (1929). A more technological connection can be extracted from Alan Speigel’s claim of Ulysses’s ‘Circe’ episode, that Joyce “projects the unconscious life of his protagonists outward, and all memory and desire seem to shift and glide before the eye of the reader in a dramatic and fully externalized form.” The connection of thoughts and “projection” can also be seen during the memory sequences of Portrait. Remembering often occurs in conjunction with the imagery of light sources, such as when Stephen thinks back to “the firelight on the wall of the infirmary where he lay sick”. The light helps to ‘cast’ the memory back into Stephen’s consciousness, as a cinema projector similarly reclaims the past by reproducing its image. Another example can be seen when Stephen remembers his childhood appearance: “It was strange to see his small body appear again for a moment: a little body in a grey belted suit.” This idea of Stephen seeing himself as a distanced external image adheres strongly to an aesthetic of projection. Finally, specific memories are also framed like cinematic shots. When thinking of his friend Cranly, Stephen can “never raise his mind the entire image of his body, but only the image of the head and face.” As with the legs and feet being cut off during the football match, this disconnected head is reminiscent of the camera frame cutting off parts of the body. These are only a small number of examples, but Joyce’s imagery of memory throughout the novel appears consistently comparable with equivalent cinematic techniques.

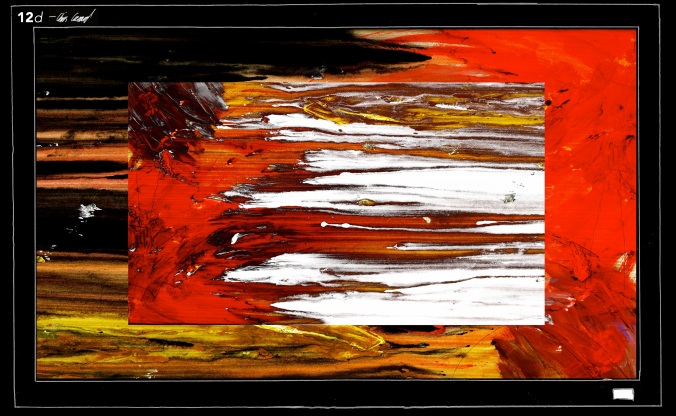

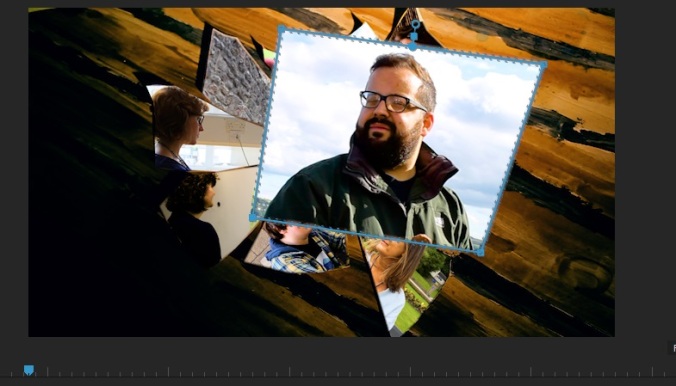

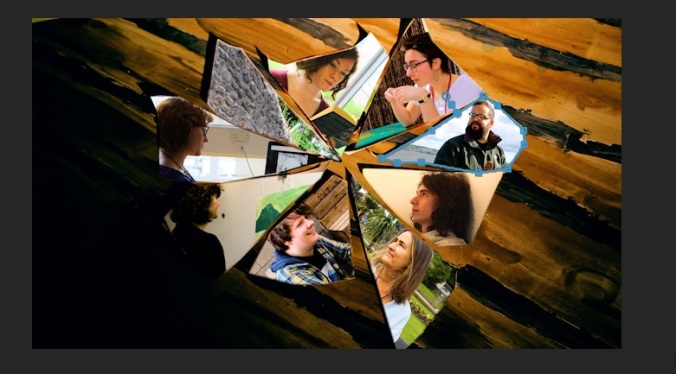

It is important to note however, that these are only comparisons. According to Spiegel, Joyce was not explicitly influenced by cinema, but rather the parallels of style that exist between the medium and the writer are due to both working on the same topics. This question of influence or parallel is beyond the purview of this essay. However, there is truth in cinema and Joycean technique sharing common themes not only in specific imagery (as seen so far), but in a broader sense of structure and intention. The very nature of cinema is temporal, the control and manipulation of time being its lifeblood, similar to the flowing time periods of Portrait. In Joyce’s original 1904 draft of Portrait he discusses the aging process as: “a fluid succession of presents, the development of an entity of which our actual present is a phase only.” This idea of fluidity is transferred over to the 1914 publication, with Stephen’s world comprised of these multiples “phases” of time which overlap and flow into one another. This is similar to Susan Sontag’s theories on photography. She claims “photography reinforces a nominalist view of social reality as consisting of small units of an apparently infinite number.” The compilation of these discrete units can be seen in a photo album, or photo book, which Sontag claims as the “most influential and way of arranging photographs, thereby guaranteeing them longevity”. A strong parallel can be seen between this and the basic structure of Portrait. Stephen’s “small units” of memories, different discrete parts of time, are brought adjacent to one another into a fluid whole. Spiegel’s ideas of the “temporalization of space”, making time a physical landscape, appear to be in agreement with this theory, with the “landscape” simply being a grander term than a photo album. Sontag, however, inaccurately claims that this makes reality “opaque”, and that it “denies interconnectedness”. Within Joyce’s work this is evidently not the case. Each memory is collected in order to provide new insight into Stephen’s present. In the following extract, filmed as a companion piece to this essay, Stephen jealously looks at his potential sweetheart:

Rude brutal anger routed the last lingering instant of ecstasy from

his soul. It broke up violently her fair image and flung the fragments

on all sides. On all sides distorted reflections of her image started

from his memory: the flower girl in the ragged dress with damp course

hair and a hoyden’s face who had called herself his own girl and begged

his handsel, the kitchen-girl in the next house who sang over the clatter

of her plates, with the drawl of a country singer, the first bars of By

Killarney’s Lakes and Fells, a girl who had laughed gaily to see him

stumble when the iron grating in the footpath near Cork Hill had caught

the broken sole of his shoe, a girl he had glanced at, attracted by her small

ripe mouth, as she passed out of Jacob’s biscuit factory, who had cried to

him over her shoulder.

Multiple images from Stephen’s past are physically laid out in front of his eyes, spatializing the past in a fashion almost identical to a set of photographs. The remembered images connect to his current experience with new found relevance. Each girl is one Stephen had a similar romantic or sexual desire for, and had been unable to act out that desire, with the complete picture being one of jealous frustration. Each individual image interacts with those around it to create a meaningful composite whole. Obviously Sontag’s theories are about photography not Joyce’s work, but showing photographs of people/locations from different times would similarly create thematic links and contrasts, so it appears that while she denies photography’s “interconnectedness”, her photo book idea is a perfect analogy to Portrait.

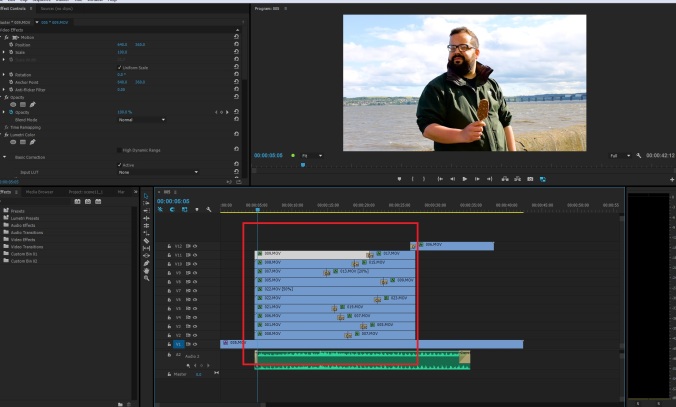

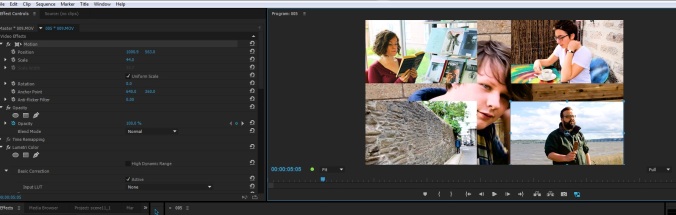

While Sontag’s ideas are on photography, in many ways her “photo book” is the precursor to cinema, as a film is similarly a composite whole made of collected time. This is demonstrated in my accompanying short film, as the preceding extract is transferred into equivalent cinematic techniques, bringing the “memories”, shot at different times, together into a single frame . Film theorist Laura Mulvey explains this process as “Film time [being] extended and remixed out of [its] original context”. Joyce’s role in this comparison changes from a photo collector to a cinematic editor whose “work personifies the reordering and transforming of raw material”. Spiegel similarly unites the cinematic novelist and the filmmaker’s ability to “cut up space and splice” the results together. Mulvey, however, does not believe the editor reorders reality itself; instead they transform the subjective reality captured by the camera. By combining the idea of the cinema as an “image of reality across time” with reality being “unable to escape the human consciousness”, Mulvey implies that cinema is a capturing of this very human consciousness rather than an objective certainty. This relates to existing critical theory on Joyce’s work, specifically Maud Ellmann’s conception of Portrait not as an attempt to “express, represent, reconstitute or describe ‘experience’ or ‘reality’, but to construct it.” The world of both the cinema and of Portrait is one inspired by reality, but not of it. This idea appears to originate within the text itself, when Stephen talks of how a person sees the world, expounding:

. Film theorist Laura Mulvey explains this process as “Film time [being] extended and remixed out of [its] original context”. Joyce’s role in this comparison changes from a photo collector to a cinematic editor whose “work personifies the reordering and transforming of raw material”. Spiegel similarly unites the cinematic novelist and the filmmaker’s ability to “cut up space and splice” the results together. Mulvey, however, does not believe the editor reorders reality itself; instead they transform the subjective reality captured by the camera. By combining the idea of the cinema as an “image of reality across time” with reality being “unable to escape the human consciousness”, Mulvey implies that cinema is a capturing of this very human consciousness rather than an objective certainty. This relates to existing critical theory on Joyce’s work, specifically Maud Ellmann’s conception of Portrait not as an attempt to “express, represent, reconstitute or describe ‘experience’ or ‘reality’, but to construct it.” The world of both the cinema and of Portrait is one inspired by reality, but not of it. This idea appears to originate within the text itself, when Stephen talks of how a person sees the world, expounding:

In order to see that basket […] your mind first of all separates the

basket from the rest of the visible universe which is not the basket.

The first phase of apprehension is a bounding line drawn about the

object to be apprehended. An esthetic image is presented to us either in

space or in time. […] Temporal or spatial, the esthetic image is first

luminously apprehended as self-bounded and self-contained upon the

immeasurable background of space or which is not it. You apprehended it

as one thing.

Once one has focused on an individual object and separated it from its surroundings, then it is no longer part of objective reality. Naturally the world has no framing devices, those we observe are created by human perception itself. Just as a film is no longer the subject as their image ceases to exist in the physical world, Stephen’s memories are no longer “really” occurring as they are removed from their original context. Both the cinematic image and the Joycean memory are moments “removed from the continuity of historical time.”

The fact they are not representative of objective reality brings in a level of uncertainty to Joyce and cinema, allowing mistakes or even lies to be propagated. Ellmann explores a specific example of this within Stephen’s train journey in Chapter 2: “Stephen was once again seated beside his father in the corner of a railway carriage at Kingsbridge.” She focuses on the inaccurate wording, noting:

‘Once again’ is a curious sleight of hand: Stephen has never shared

a railway carriage with his father in the text before. This is a first time

masquerading as a repetition. […] This passage does not repeat a real

event, but a dream that Stephen had at Clongowes. […] Just as the

beginning of Stephen’s story is another story, so here the real train evolves

out of the dream. This order makes a fiction of experience.

If the earlier example is a dream, then the mental faculty which labelled this as a “repetition” is flawed. When decided whether to accept a religious vocation, Stephen’s memory similarly fails to picture the face of “Lantern Jaws”, seeing it as “an undefined face or colour of a face” which forms into an “eyeless and sour-favoured and devout” face with little physical detail. Earlier he attempts to reclaim a memory of his youth only to discover it “grew dim” and he could not “call forth its vivid moments”. These examples of memory “degenerating into images and echoes of themselves” all effect Stephen’s present decisions and feelings. Joyce is therefore commenting upon the fragility of memory and how this frailty can influence decisions made years on. Mulvey tackles a similar idea in her work. If the composite whole of a film is the “art of the index”, it is an index comprised of “human consciousness”, and therefore cannot be objectively reliable. When discussing Man with a Movie Camera, Mulvey quotes the director Dziga Vertov’s assertion that cinema renders “uncertainity more certain.” This implies cinema fixes the human consciousness into an objective reality, the film itself, allowing for the transfer of meaning. MWAMC however, does not display the “real” world, instead being a work of  Soviet propaganda. It is a City Symphony film, displaying life in Russian cities, and the specific shots used only show the good sides of such a life. The time captured, the memories used, are all of happy and productive citizens, proving the “meaning” imparted by the cinema need not be the objective truth. Similarly Joyce allows for inaccurate memories which falsely influence Stephen when he reinterprets them. For instance, when remembering his school years Stephen “recognized scenes and persons yet he was conscious that he had failed to perceive some vital circumstance in them”, replaying these memories to gain new insight into his childhood experiences to help him decide whether to become a priest. Ellmann claims this as similar to Freud’s ideas of repressed memories and delayed action, a theory Mulvey also uses to describe cinema. Mulvey states the “storage function [of cinema] may be compared to the memory left in the unconscious by an incident lost to consciousness. […] Both need to be deciphered retrospectively across delayed time”, precisely paralleling Ellmann’s evocation of Joyce’s “literature administering deferred effects”. Joyce uses this psychoanalytic theory to comment upon the unreliable of memory, an unreliability that is deeply ingrained into the very basic nature of film itself. Spiegel is therefore correct, cinema and Joyce are both working from the same basis, the human experience of memory, with their techniques and structure being exceptionally similar to the extent that parallel critical theory exists on both.

Soviet propaganda. It is a City Symphony film, displaying life in Russian cities, and the specific shots used only show the good sides of such a life. The time captured, the memories used, are all of happy and productive citizens, proving the “meaning” imparted by the cinema need not be the objective truth. Similarly Joyce allows for inaccurate memories which falsely influence Stephen when he reinterprets them. For instance, when remembering his school years Stephen “recognized scenes and persons yet he was conscious that he had failed to perceive some vital circumstance in them”, replaying these memories to gain new insight into his childhood experiences to help him decide whether to become a priest. Ellmann claims this as similar to Freud’s ideas of repressed memories and delayed action, a theory Mulvey also uses to describe cinema. Mulvey states the “storage function [of cinema] may be compared to the memory left in the unconscious by an incident lost to consciousness. […] Both need to be deciphered retrospectively across delayed time”, precisely paralleling Ellmann’s evocation of Joyce’s “literature administering deferred effects”. Joyce uses this psychoanalytic theory to comment upon the unreliable of memory, an unreliability that is deeply ingrained into the very basic nature of film itself. Spiegel is therefore correct, cinema and Joyce are both working from the same basis, the human experience of memory, with their techniques and structure being exceptionally similar to the extent that parallel critical theory exists on both.

Portrait then is a perfect example of Joyce’s cinematic similarities, whether conscious or not. The specific imagery of Stephen’s experiences matches with examples which can be seen in various early silent films, especially when exploring the faculty of memory. Joyce’s memory imagery and structure have a particular affinity with the cinema, but it is clear that this is neither an accident nor Joyce simply copying cinematic technique. Instead it is a deeper thematic and almost philosophical connection, each using the unreliability and visually dense properties of the subjective experience of memory in equivalent manners. This solidifies film’s reputation as the modernist medium, as the same thought processes Joyce used to write Portrait are those at the basis of cinema. Memory therefore becomes the bridge that unites Joyce, the cinema, and their respective critical theories.

As I always note with re-printed essays, this was written one year ago. I stand by my points, but some could have be elucidated more precisely and more accurate cinematic examples.

style is directly comparable to cinematic technique. His imagery often draws on the relationship of light and shadow, even from his earliest childhood works. While his luminous imagery may have begun in the era of the zoetrope and magic lantern, the more complex optical descriptions in Joyce’s later work contain direct parallels with cinema itself. Specifically, this essay will examine 1914’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Here, such cinematic imagery is mixed with another filmic technique: the flexibility of time. Portrait’s temporal continuity is fluid, as the novel smoothly transitions between periods of its protagonist’s life, allowing the reader to “literally wander about in time, as if it were part of a solid and seemingly permanent landscape.” This temporal fluidity is a central tenet of the cinema. Within the plot of a typical film there are often flashbacks and flash-forwards, but even the most basic film editing requires the combination of scenes and shots filmed at different times. This renders any film into a collection of different moments, similar to Stephen Dedalus’ fragmented history in Portrait. The novel’s temporal jumps, as well as its particularly cinematic imagery, are most notable when the narrative becomes a subjective memory of earlier events. This essay will therefore examine these extracts in order to explore the novel’s relationship with the cinema, and will attempt to bridge the gap between existing critical theory on both Joyce and film through their mutual association with the faculty of memory.

style is directly comparable to cinematic technique. His imagery often draws on the relationship of light and shadow, even from his earliest childhood works. While his luminous imagery may have begun in the era of the zoetrope and magic lantern, the more complex optical descriptions in Joyce’s later work contain direct parallels with cinema itself. Specifically, this essay will examine 1914’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Here, such cinematic imagery is mixed with another filmic technique: the flexibility of time. Portrait’s temporal continuity is fluid, as the novel smoothly transitions between periods of its protagonist’s life, allowing the reader to “literally wander about in time, as if it were part of a solid and seemingly permanent landscape.” This temporal fluidity is a central tenet of the cinema. Within the plot of a typical film there are often flashbacks and flash-forwards, but even the most basic film editing requires the combination of scenes and shots filmed at different times. This renders any film into a collection of different moments, similar to Stephen Dedalus’ fragmented history in Portrait. The novel’s temporal jumps, as well as its particularly cinematic imagery, are most notable when the narrative becomes a subjective memory of earlier events. This essay will therefore examine these extracts in order to explore the novel’s relationship with the cinema, and will attempt to bridge the gap between existing critical theory on both Joyce and film through their mutual association with the faculty of memory. world. The experience of watching other boys playing football is described: “Then Jack Lawton’s yellow boots dodged out the ball and all the other boots and legs ran after.” The legs and boots appear independently to the boys they belong to. This example of synecdoche also parallels the cinematic close-up. Often parts of the body will be shown alone, as the action cuts between them , fragmenting the body in a similar way to Joyce’s language.

world. The experience of watching other boys playing football is described: “Then Jack Lawton’s yellow boots dodged out the ball and all the other boots and legs ran after.” The legs and boots appear independently to the boys they belong to. This example of synecdoche also parallels the cinematic close-up. Often parts of the body will be shown alone, as the action cuts between them , fragmenting the body in a similar way to Joyce’s language. grey sky so high up.” Keith Williams compares this distorted image to a similar scene in F.W. Murnau’s 1924 film The Last Laugh, in which a janitor’s vision is similarly obscured due to poor eye-sight, with his struggle to read forcing a letter’s contents to appear as individual words. These are objective “facts” of Stephen’s world, however; the next layer of his interiority comes from his interpretation of such experiences. When performing a play:

grey sky so high up.” Keith Williams compares this distorted image to a similar scene in F.W. Murnau’s 1924 film The Last Laugh, in which a janitor’s vision is similarly obscured due to poor eye-sight, with his struggle to read forcing a letter’s contents to appear as individual words. These are objective “facts” of Stephen’s world, however; the next layer of his interiority comes from his interpretation of such experiences. When performing a play:

sequences, the most notable being when Stephen is taunted by Satyrs, similar to many early trick films of demonic transformation. Due to these dreams being wholly fictional constructions, the representation of memory is rendered unique due to its transformation of the real. Joyce’s manipulation of memories takes events which have occurred and defamiliarises them, turning simple human moments into visually dynamic experiences. Such memories “pass sharply and swiftly before [Stephen’s] mind”, almost becoming his reality as he retreats within them to the point that he must be re-awoken by a violent external influence. When remembering his arrival to Clongowes, Stephen is unaware of a loud football match around him, only brought back to the present by being “caught in the whirl of a scrimmage”. This implies that the memories overlay on top of Stephen’s current experiences, obscuring his view.

sequences, the most notable being when Stephen is taunted by Satyrs, similar to many early trick films of demonic transformation. Due to these dreams being wholly fictional constructions, the representation of memory is rendered unique due to its transformation of the real. Joyce’s manipulation of memories takes events which have occurred and defamiliarises them, turning simple human moments into visually dynamic experiences. Such memories “pass sharply and swiftly before [Stephen’s] mind”, almost becoming his reality as he retreats within them to the point that he must be re-awoken by a violent external influence. When remembering his arrival to Clongowes, Stephen is unaware of a loud football match around him, only brought back to the present by being “caught in the whirl of a scrimmage”. This implies that the memories overlay on top of Stephen’s current experiences, obscuring his view. faces creates a multi-layered image, one covering the other. In silent cinema, this effect was comparatively common, for example allowing the camera to tower over cities in Man with a Movie Camera (1929). A more technological connection can be extracted from Alan Speigel’s claim of Ulysses’s ‘Circe’ episode, that Joyce “projects the unconscious life of his protagonists outward, and all memory and desire seem to shift and glide before the eye of the reader in a dramatic and fully externalized form.” The connection of thoughts and “projection” can also be seen during the memory sequences of Portrait. Remembering often occurs in conjunction with the imagery of light sources, such as when Stephen thinks back to “the firelight on the wall of the infirmary where he lay sick”. The light helps to ‘cast’ the memory back into Stephen’s consciousness, as a cinema projector similarly reclaims the past by reproducing its image. Another example can be seen when Stephen remembers his childhood appearance: “It was strange to see his small body appear again for a moment: a little body in a grey belted suit.” This idea of Stephen seeing himself as a distanced external image adheres strongly to an aesthetic of projection. Finally, specific memories are also framed like cinematic shots. When thinking of his friend Cranly, Stephen can “never raise his mind the entire image of his body, but only the image of the head and face.” As with the legs and feet being cut off during the football match, this disconnected head is reminiscent of the camera frame cutting off parts of the body. These are only a small number of examples, but Joyce’s imagery of memory throughout the novel appears consistently comparable with equivalent cinematic techniques.

faces creates a multi-layered image, one covering the other. In silent cinema, this effect was comparatively common, for example allowing the camera to tower over cities in Man with a Movie Camera (1929). A more technological connection can be extracted from Alan Speigel’s claim of Ulysses’s ‘Circe’ episode, that Joyce “projects the unconscious life of his protagonists outward, and all memory and desire seem to shift and glide before the eye of the reader in a dramatic and fully externalized form.” The connection of thoughts and “projection” can also be seen during the memory sequences of Portrait. Remembering often occurs in conjunction with the imagery of light sources, such as when Stephen thinks back to “the firelight on the wall of the infirmary where he lay sick”. The light helps to ‘cast’ the memory back into Stephen’s consciousness, as a cinema projector similarly reclaims the past by reproducing its image. Another example can be seen when Stephen remembers his childhood appearance: “It was strange to see his small body appear again for a moment: a little body in a grey belted suit.” This idea of Stephen seeing himself as a distanced external image adheres strongly to an aesthetic of projection. Finally, specific memories are also framed like cinematic shots. When thinking of his friend Cranly, Stephen can “never raise his mind the entire image of his body, but only the image of the head and face.” As with the legs and feet being cut off during the football match, this disconnected head is reminiscent of the camera frame cutting off parts of the body. These are only a small number of examples, but Joyce’s imagery of memory throughout the novel appears consistently comparable with equivalent cinematic techniques. . Film theorist Laura Mulvey explains this process as “Film time [being] extended and remixed out of [its] original context”. Joyce’s role in this comparison changes from a photo collector to a cinematic editor whose “work personifies the reordering and transforming of raw material”. Spiegel similarly unites the cinematic novelist and the filmmaker’s ability to “cut up space and splice” the results together. Mulvey, however, does not believe the editor reorders reality itself; instead they transform the subjective reality captured by the camera. By combining the idea of the cinema as an “image of reality across time” with reality being “unable to escape the human consciousness”, Mulvey implies that cinema is a capturing of this very human consciousness rather than an objective certainty. This relates to existing critical theory on Joyce’s work, specifically Maud Ellmann’s conception of Portrait not as an attempt to “express, represent, reconstitute or describe ‘experience’ or ‘reality’, but to construct it.” The world of both the cinema and of Portrait is one inspired by reality, but not of it. This idea appears to originate within the text itself, when Stephen talks of how a person sees the world, expounding:

. Film theorist Laura Mulvey explains this process as “Film time [being] extended and remixed out of [its] original context”. Joyce’s role in this comparison changes from a photo collector to a cinematic editor whose “work personifies the reordering and transforming of raw material”. Spiegel similarly unites the cinematic novelist and the filmmaker’s ability to “cut up space and splice” the results together. Mulvey, however, does not believe the editor reorders reality itself; instead they transform the subjective reality captured by the camera. By combining the idea of the cinema as an “image of reality across time” with reality being “unable to escape the human consciousness”, Mulvey implies that cinema is a capturing of this very human consciousness rather than an objective certainty. This relates to existing critical theory on Joyce’s work, specifically Maud Ellmann’s conception of Portrait not as an attempt to “express, represent, reconstitute or describe ‘experience’ or ‘reality’, but to construct it.” The world of both the cinema and of Portrait is one inspired by reality, but not of it. This idea appears to originate within the text itself, when Stephen talks of how a person sees the world, expounding: Soviet propaganda. It is a City Symphony film, displaying life in Russian cities, and the specific shots used only show the good sides of such a life. The time captured, the memories used, are all of happy and productive citizens, proving the “meaning” imparted by the cinema need not be the objective truth. Similarly Joyce allows for inaccurate memories which falsely influence Stephen when he reinterprets them. For instance, when remembering his school years Stephen “recognized scenes and persons yet he was conscious that he had failed to perceive some vital circumstance in them”, replaying these memories to gain new insight into his childhood experiences to help him decide whether to become a priest. Ellmann claims this as similar to Freud’s ideas of repressed memories and delayed action, a theory Mulvey also uses to describe cinema. Mulvey states the “storage function [of cinema] may be compared to the memory left in the unconscious by an incident lost to consciousness. […] Both need to be deciphered retrospectively across delayed time”, precisely paralleling Ellmann’s evocation of Joyce’s “literature administering deferred effects”. Joyce uses this psychoanalytic theory to comment upon the unreliable of memory, an unreliability that is deeply ingrained into the very basic nature of film itself. Spiegel is therefore correct, cinema and Joyce are both working from the same basis, the human experience of memory, with their techniques and structure being exceptionally similar to the extent that parallel critical theory exists on both.

Soviet propaganda. It is a City Symphony film, displaying life in Russian cities, and the specific shots used only show the good sides of such a life. The time captured, the memories used, are all of happy and productive citizens, proving the “meaning” imparted by the cinema need not be the objective truth. Similarly Joyce allows for inaccurate memories which falsely influence Stephen when he reinterprets them. For instance, when remembering his school years Stephen “recognized scenes and persons yet he was conscious that he had failed to perceive some vital circumstance in them”, replaying these memories to gain new insight into his childhood experiences to help him decide whether to become a priest. Ellmann claims this as similar to Freud’s ideas of repressed memories and delayed action, a theory Mulvey also uses to describe cinema. Mulvey states the “storage function [of cinema] may be compared to the memory left in the unconscious by an incident lost to consciousness. […] Both need to be deciphered retrospectively across delayed time”, precisely paralleling Ellmann’s evocation of Joyce’s “literature administering deferred effects”. Joyce uses this psychoanalytic theory to comment upon the unreliable of memory, an unreliability that is deeply ingrained into the very basic nature of film itself. Spiegel is therefore correct, cinema and Joyce are both working from the same basis, the human experience of memory, with their techniques and structure being exceptionally similar to the extent that parallel critical theory exists on both.